First, imagine that you are a time-traveler living in the year 3019 and you wanted to travel back one hundred years ago to observe what the world was like in 2019. Your chief concern would be to blend in so as not to cause a complete and total breakdown of normal life as we know it. What would you wear? How would you wear it? What sources would you use to decide the answers to those questions?

You might take a look at famous photographs that have survived from that period, images from fashion designers, photographs of ordinary people, or perhaps examples of clothing that were saved in a museum. All of these “artifacts” are from the year 2019 however, only some of them will help you in achieving your goal of blending in. Additionally, you would notice in your research that fashion can change rapidly over just a few decades. No one would mistake a 1970s powder blue suit as belonging in the early 2000s.

A less glaring example though might be the case of “blue jeans”. Looking at your collection of photographs you’ll likely find plenty of different colors of jeans that people are wearing. But which one is the most common? No one is going to look at a pair of blue jeans and remark about the color. It is the standard and all others are deviations from it.

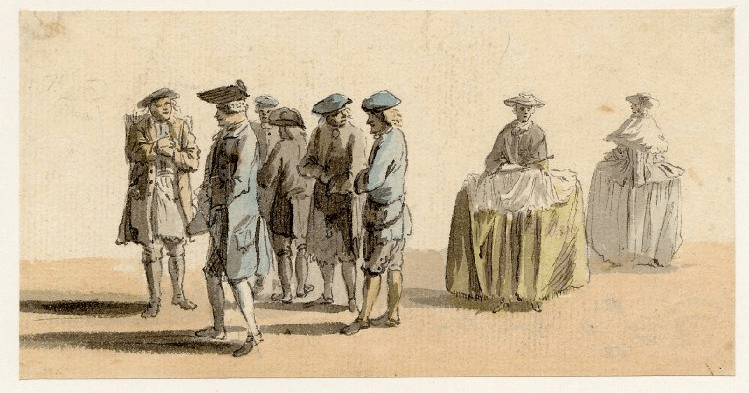

This same approach should be taken by the living historian that wants to do justice to his or her subject. The goal of your representation should be to become “invisible”, to blend in perfectly with the original culture that you are portraying. Of course there were exceptions, people have deviated from the norm since the beginning of time however, your goal should be to educate the public on what the average member of your chosen group looked like. Just because you found two paintings that showed a person wearing a beard in the middle of the 18th century, doesn’t discount the thousands of paintings, etchings, drawings, and written descriptions indicating that 98% of all Europeans and Americans in the colonial period were clean-shaven. Generally speaking, if you have to have a backstory for why you selected an aspect of your presentation you might want to reconsider it.

As a caveat though, it is important to remember that we are all human and all of us in the hobby are in various stages of improving our kit. None of us have a perfect rendition of an accurate mid-18th highlander however, the key is to be honest about your presentation. If shaving your beard would cause a serious issue in your household by all means keep it. But when interacting with the public, tell them what areas aren’t quite right or are our best guesses at what it might have looked like. Just don’t create a story about how you are representing the “one guy” that acquired such and such piece of equipment while “serving as a mercenary in the Ottoman Empire and brought it back to your native country because you like it better”. Embrace the invisibility.

Guidelines for “Invisibility” as a 1730s – 1740s Highland Scotsman

- Bonnets should be an indigo blue wool, preferably knitted.

- Jackets and Waistcoats should be of a fuller mid-century cut but shorter.

- Brighter and more intricate tartans indicated a higher economic status whereas a poorer Scot would have worn more earthen colors with simpler weaves. White (undyed) wool was also associated with poorer status.

- Your weapons and clothing should be in sync and match the economic status of the person you are representing. A highlander only clad in a shirt and plaid would not be carrying pistols or a fancy basket-hilted broadsword.

- Obvious anachronisms such as modern eyewear, watches, shoes, jewelry, and tobacco use should be avoided.

- If possible, be cleanshaven.

- Do not use “Braveheart-style” blue woad face paint. It was already an anachronism by the Medieval Ages.

- Ask questions, look for primary source inspiration, constantly look for areas to improve, and have fun!